Raising alternative grounds of objection under s 17(1)(a) and (b) is of limited utility when the alleged unlawfulness is breach of the Fair Trading Act or passing off. If the opponent establishes s 17(1)(a) as a ground of objection, registration will be prohibited. If the opponent does not establish that s 17(1)(a) applies, then it is well established that the higher threshold for establishing a breach of the Fair Trading Act or the tort of passing off in s 17(1)(b) will not be met.1

Never were truer words written in an IPONZ trade mark decision. And yet, despite Assistant Commissioner Casey KC’s clear warning in 2016, and numerous decisions since then which have repeated the warning,2 parties have, over the last eight years, continued to needlessly plead breach of the Fair Trading Act 1986 (FTA) and passing off as grounds of opposition or invalidity alongside section 17(1)(a).

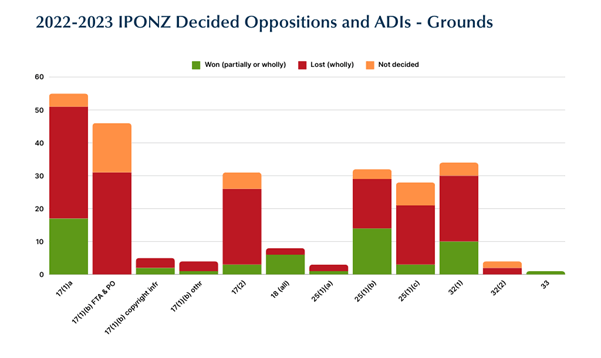

But this article is not about why pleading breach of FTA and passing off as grounds of opposition and invalidity alongside section 17(1)(a) is the very definition of an exercise in futility (as well as a magnet for increased or decreased costs awards); not exclusively anyway. Rather, this article looks more broadly at the merits (or otherwise) of all grounds of opposition and invalidity considered in IPONZ decisions published on NZLII in 2022-2023 to see what, if any, insights might be gleaned.

At this point, I must admit that that I was inspired to write this review by the recent article penned by Jenny Mackie of Michael Buck IP3 which, as well remarking on IP Australia’s fee review, analysed the success and failure rates of grounds in IP Australia trade mark opposition proceedings in 2023. With Jenny’s consent, there are obvious similarities between her review and mine, including methodology and colours used for the charts. Hopefully these similarities will not only make it straightforward to read the articles side by side but also to discern the similarities and differences between jurisdictions. My sincere thanks to Jenny.

Grounds of opposition and invalidity – methodology

I looked at every opposition and invalidity proceeding that resulted in an Assistant Commissioner’s decision published on NZLII in 2022 and 2023. I noted the grounds pleaded as recorded in the published decisions, the grounds that were successful (wholly or partially), the grounds that were not successful at all, and the grounds that were not decided at the Assistant Commissioners’ discretion. To the extent any grounds were pleaded in a notice of opposition or application for declaration of invalidity but not recorded in the published decisions, they are not reflected in the analysis.

I reviewed two years’ worth of decisions as the volume of decisions issued in New Zealand per year is not as high as in Australia. To put this into actual numbers, I reviewed 61 decisions (2022 – 25 decisions; 2023 – 36 decisions), while Jenny reviewed 129 from 2023 alone. While I could have analysed 2021 and 2022 decisions to bolster my sample size, I considered two years’ worth of data should be sufficient to yield potentially meaningful insights.

The analysis does not take into account any appeals of Assistant Commissioner’s decisions to the New Zealand High Court or above.

Grounds of opposition and invalidity – analysis

Overall summary

Of the 61 decisions reviewed, 44 were decided oppositions and 17 were decided invalidity applications. Although the bulk of the decisions were decided ‘on the papers’ at the election of both parties, or ‘on the papers’ at the election of one party and by written submissions at the election of the other party, the decisions did not reveal any data that might suggest one hearing option was more likely to be successful than another hearing option.

The most popular grounds pleaded were (in descending order):

- s17(1)(a), use of mark or part of mark likely to deceive or cause confusion (equivalent of s60, Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth));

- s32(1), not the owner (equivalent of s58 and s58A, Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth));

- s25(1)(b), confusingly similar to registered mark (part equivalent of s44, Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth));

- s17(2), bad faith (equivalent of s62A, Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth))

- s25(1)(c), well known mark (no equivalent under Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth));

- s17(1)(b), contrary to law – passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act (equivalent of s42b, Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth)) (noting that passing off was only pleaded in conjunction with breach of the FTA and only in approx. two thirds of the cases in which breach of the Fair Trading Act was pleaded).

As can be seen in the above chart, the top five most successful grounds of those pleaded on 10 occasions or more were (in descending order): s25(1)(b), s17(1)(a), s32(1), s25(1)(c), and s17(2).

Noticeably absent from the top five successful grounds is s17(1)(b) based on passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act. More on this shortly…

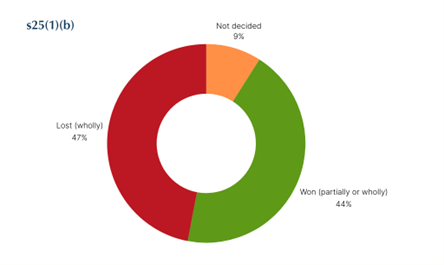

s25(1)(b) ‘confusingly similar to registered mark’

At a success rate of 44%, the position of s25(1)(b) at the top of the NZ list of successful grounds – which matches s44’s position at the top of the list in IP Australia oppositions4 – clearly demonstrates the value of having a registered right to rely on, especially in circumstances when an opponent/applicant is unwilling or unable to financially commit to pursuing a full opposition or invalidity with evidence and filing submissions or attending a hearing.

As to why s25(1)(b) was not successful, 53% of failures were due to the subject marks not being similar; 40% were attributable to either a lack of similarity between goods/services or, despite there being some degree of similarity between the subject marks, a lack of likelihood of deception or confusion; and 7% (representing only 1 decision) were attributable to pleading UK not NZ registered trade marks.

s17(1)(a) ‘use of mark or part of mark likely to deceive or cause confusion’

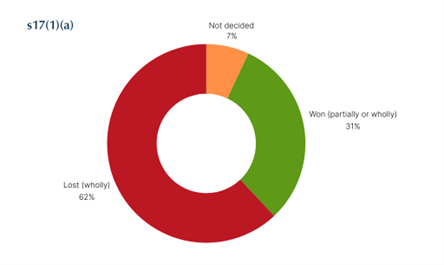

Given its position as the ‘go to’ ground of opposition and invalidity, s17(1)(a)’s success rate of 31% was (to me) surprisingly low. That said, its success rate was considerably higher than its s60 counterpart in Australia at a very poor 6%.

As to why s17(1)(a) was not successful, a whopping 62% of failures were due to insufficient evidence of reputation being filed by the opponent or applicant. Given the threshold to establish reputation is low, that is a remarkable statistic and potentially indicates opponents/applicants should think twice before pleading the ground, or amend their opposition/application to withdraw the ground either before or at the pre-hearing stage of proceedings. 12% of failures were due to inadmissible evidence (principally evidence not filed in the correct form), 9% of failures were due to the subject marks being dissimilar, and 18% of failures were due to a lack of likelihood of deception or confusion on account of dissimilar goods or services or the relevant surrounding circumstances of trade.

s32(1) ‘not the owner’

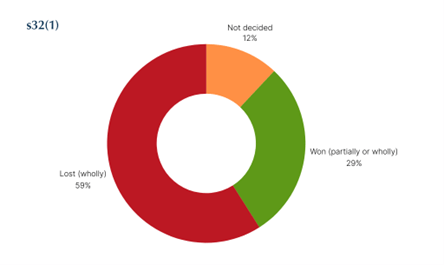

Oppositions and invalidities pleading s32(1) enjoyed a success rate of 29%, only marginally behind s17(1)(a).

Failure (or success) under s32(1) came down to one of five factors: the subject marks not being the same or substantially identical (30%), the evidence filed was inadmissible (20%), the scope of the opponent’s/applicant’s use was dissimilar to the goods or services in question (20%), insufficient evidence of prior use (25%), or the subject trade mark being distinctive and therefore capable of being owned (5%).

What the first four of these factors tend to show is that if a party is going to plead s32(1), then it needs to do so with establishing the legal tests very much in mind. In other words, it is not a ‘disposable’ ground as section 17(1)(b) passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act might be.

s25(1)(c) ‘well known mark’ and s17(2) ‘bad faith’

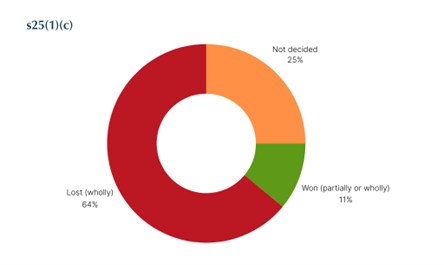

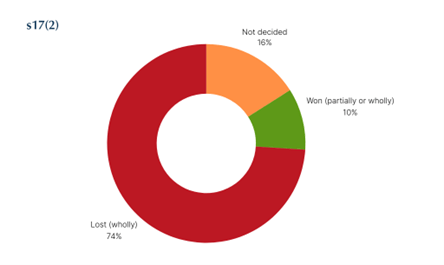

Oppositions and invalidities pleading s25(1)(c) and s17(2) enjoyed the very low success rates of 11% and 10% respectively.

Success or failure under s25(1)(c) and s17(2) universally comes down to a question of evidence given the acknowledged high thresholds to succeed under these grounds. Personally, I was surprised at how often s17(2) – bad faith – is pleaded given the seriousness of the allegations being made under this ground. It seems to be approached as a ‘throw-away’ ground without much care and attention as to why it is being pleaded or the evidential threshold to meet. Again, I believe parties would be well served by not pleading s25(1)(c) or s17(2) unless there is sufficiently clear indication at the time of pleading that the background facts clearly support the ground(s); or, if they must, then not pursuing these grounds at a hearing if the evidence does not objectively support the ground(s).

s17(1)(b) ‘passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act 1986’

Finally, we get to s17(1)(b), where the focus of this analysis are the allegations of passing off and breach of the Fair Trading Act (FTA), not copyright infringement and any other allegations brought under s17(1)(b) (such as contrary to equity).

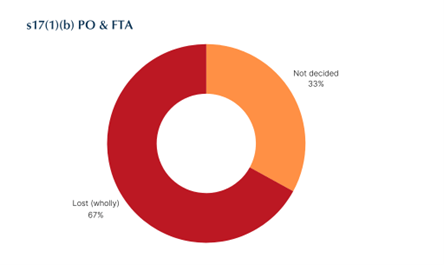

Passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act was pleaded no less than 46 times across the 61 decisions reviewed (so in 75% of cases); however, not once – as Jenny Mackie remarked of s42(b) – did the ground lead its host to victory. More specifically, passing off was unsuccessful on 15 occasions and not decided on in a further 5; while breach of the FTA was unsuccessful on 16 occasions and not decided on in a further 10.

Why isn’t s17(1(b) a winner? Well, on the occasions that passing off and/or breach of the FTA were pleaded alongside s17(1)(a) and were unsuccessful, the s17(1)(a) ground of opposition or invalidity was also unsuccessful. It was not necessary then to decide the passing off and/or breach of FTA allegations under s17(1)(b) as the outcome of the s17(1)(a) ground had pre-determined the outcome of the s17(1)(b) ground. On the occasions that passing off and/or breach of the FTA were pleaded alongside s17(1)(a) and were not decided, this was because the s17(1)(a) ground had either succeeded, failed or not been decided due to success under another ground – all of which rendered deciding allegations of passing off and/or breach of the FTA under s17(1)(b) unnecessary.

Assistant Commissioner Casey KC’s words in Shenzen Motoma Power Co Ltd v Motorola Trademark Holdings LLC thus ring one hundred percent true: pleading passing off and/or breach of the FTA under s17(1)(b) alongside s17(1)(a) are of limited utility. In fact, zero utility.

Conclusion

The top five most popular and successful grounds pleaded in decided oppositions and invalidity applications published on NZLII in New Zealand in 2022 and 2023 were: s25(1)(b), s17(1)(a), s32(1), s25(1)(c), and s17(2). The first three were successful by some margin over the fourth and fifth grounds, establishing their value and place in oppositions and invalidity applications.

Other grounds also enjoyed fair success rates – such as infringement of copyright under s17(1)(b) (40%) and section 18 (lack of distinctiveness/descriptive mark) (75%). However, these grounds are very rarely pleaded. Such decisions as there are on these grounds in 2022-2023, however, do give useful insights into how parties can achieve success.

Much less successful were the grounds under s25(1)(c) (well known mark) and s17(2) (bad faith), illustrating the importance of (a) filing appropriate evidence in support of these grounds, and (b) withdrawing the grounds before the hearing if the evidence filed does not support them.

Languishing firmly at the bottom of the success list is s17(1)(b) based on passing off and/or breach of the Fair Trading Act. There can surely be no doubt that pleading these grounds alongside section 17(1)(a) really is the definition of an exercise in futility.

- Shenzen Motoma Power Co Ltd v Motorola Trademark Holdings LLC [2016] NZIPOTM 25 AT [78] per Assistant Commissioner Casey KC, citing Daimler AG (formerly Daimlercrysler AG) v Sany Group Ltd [2014] NZHC 532 at [49] – [51], approach generally accepted in the Court of Appeal, see Daimler AG v Sany Group Co Ltd [2015] NZCA 418 at [39] – [43].

- For example: Tyremax LP v Bridgestone Licensing Services, Inc [2017] NZIPOTM 13 at [157]-[158]; Pakton Developments Pty Ltd v Energizer Brands, LLC [2018] NZIPOTM 32 at [100]; Brandt’s Fruit Trees I, Inc. v Apple and Pear Australia Limited [2021] NZIPOTM 4 at [109]-[111]; The Premium Liquor Co. Limited v Hint, Inc. [2021] NZIPOTM 24 at [85]-[88] and recently Misipope Soliai v Hugo Boss Trade Mark Management GmbH & Co. KG [2024] NZIPOTM 9 at [18] and [75].

- https://www.mbip.com.au/will-s42b-stop-being-invited-to-the-trade-mark-opposition-party/

- Noting that s25(1)(b) on its own, or even in combination with s25(1)(a), is not an exact equivalent of s44.